“POETRY IS NOT A LUXURY”[1]: Queering the space with the artist Alex Turgeon

08/04/2021

“POETRY IS NOT A LUXURY”[1]: Queering the space with the artist Alex Turgeon

In the scope of the Kaos GL Associations’ Artist Residency Program, Ankara Queer Art, curator and writer Derya Bayraktaroğlu in conversation with an interdisciplinary artist, a poet Alex Turgeon whose works deal with the poetic space of architecture, questioning the built space and language by performing queer thought.

this-prison-house-of-poetry-where-language-incarcerates-personifying-madness-building-

formations-of-nonsense-while-keeping-the-erections-nonsensical-within

Alex Turgeon, Prison House of Poetry, 2017. Concrete poem, excerpted from artist book ’Lock Me Up’ published on the occasion of the exhibition The Ouroboros in the Cul-de-Sac, clearview Ltd., London, 2017. Courtesy of the Artist

D.B. : Alex, hi. Thank you for taking the time to talk with me. Ankara Queer Art Program was supposed to host you in Ankara, as you are one of the selected artists to attend the residency. Due to the restrictions and lockdowns, Kaos GL Association decided to give support to the artists' productions at their current places. How are you in times of the pandemic, in which stepping out of the usual living and working environment to explore and reflect is exceptional?

A.T. : I am entirely grateful for the support from Kaos GL Association at this time. The pandemic has produced a seismic shift in my life. This is not an effect unique to me, as the restrictions and lockdown policies are felt by seemingly everyone. Speaking with peers, friends and kin abroad there is a resounding commonality between everyone’s varying, and often disparate positions. This great slowing has levelled populations into a similar space of motionlessness. Of course each individual’s experience is different, and dependent on a number of corresponding attributes—which has been highlighted by the contrasting levels of access to housing, work, as well as personal and emotional safety. I am very privileged to be able to think and talk about art at this time, it's something which I have very conflicting emotions with. Safety is something that I do not take for granted; however, should not be novel. Working during this time is complicated, though the shuttering of most cultural institutions and programming has left a very real chasm in the fabric of society. I think this experience frames the importance of the arts and cultural initiatives, and the ingenuity of artists to reformulate community engagement, as an equal aspect for the wellbeing of society over all.

D.B. : Your works often deal with house. Does the new feature of isolated living and dependence on a place, have any effect on your ongoing research?

A.T. : It has made me further consider variations on the definition of the term. A house is by no means a home, even as I currently operate out of what I have begun to call my ancestral home now that I have returned to Canada. From here my perspective shifts from the house as a glyph to a definition of an interior. I am interested in the relationship, or disconnect, between the exteriority of a structure, such as a house, and its interiority as a potential site for wildness. In a way trying to understand how this new static nature of living slips along with the very real passage of time, time is standing still yet moving by quickly. There is something exceptionally Romantic about the nature of interiority, in self-reflection, the inward gaze. Through the lens of Romanticism this site of the interior becomes an opportunity for fantasy, imagination. I am trying to think of how a house can be further defined away from the ubiquitous “home button” we have come to associate with what a house looks like. To do this I am considering how interior space relates, or not, to the exterior.

Neighbourhood Watch, 2020. Wood, paper, acrylic glass, flickering candle bulbs, metal brackets and hardware. 44,5 x 42,2 x 40,2 cm. Courtesy of the Artist.

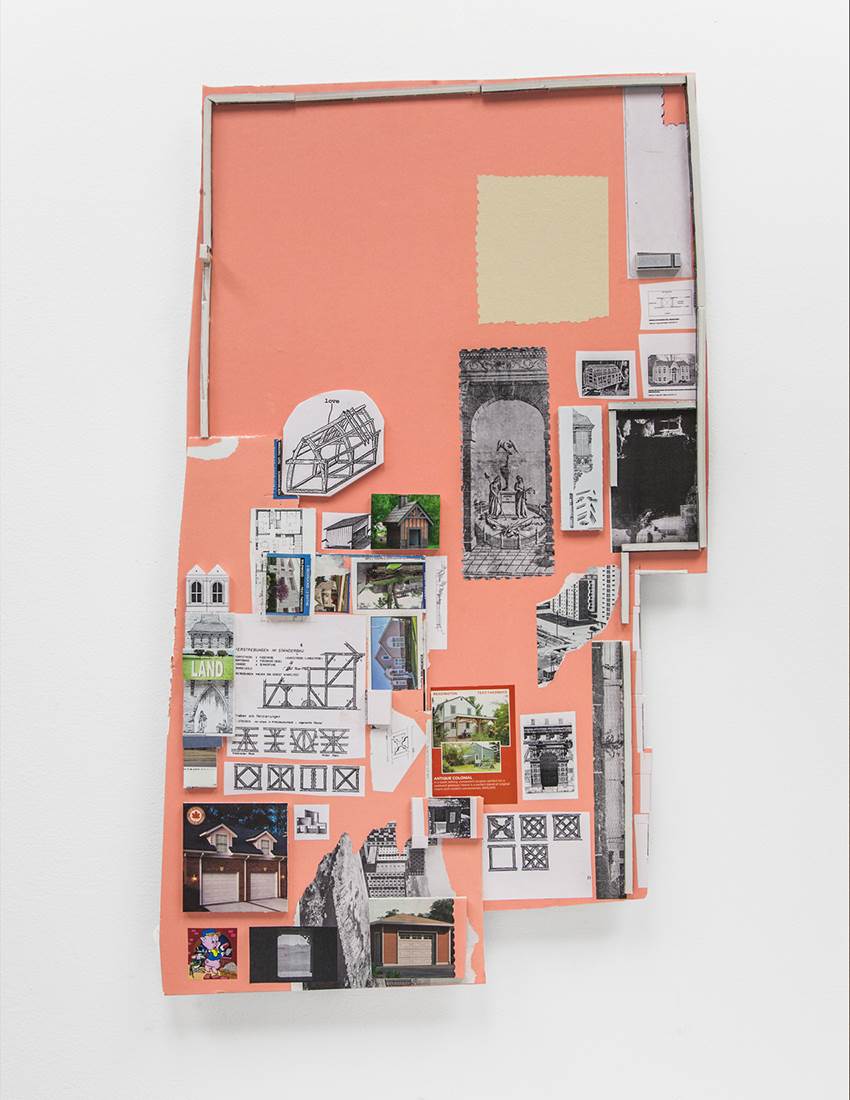

Alex Turgeon, Notes on Interiors, 2020. Collage on foam-core, 74 x 46 cm. Courtesy of the Artist

D.B. : By state policies, the nuclear family’s living place turned into the affirmed environment of survival. The ones having no place or having no will to fit in, experience enormous difficulties. Home shines out as the safest place, and concurrently, perishes as people are on streets protesting poverty and anti-democratic measures of lockdown policies. What do you foresee for the near future of 'Home Sweet Home' ?

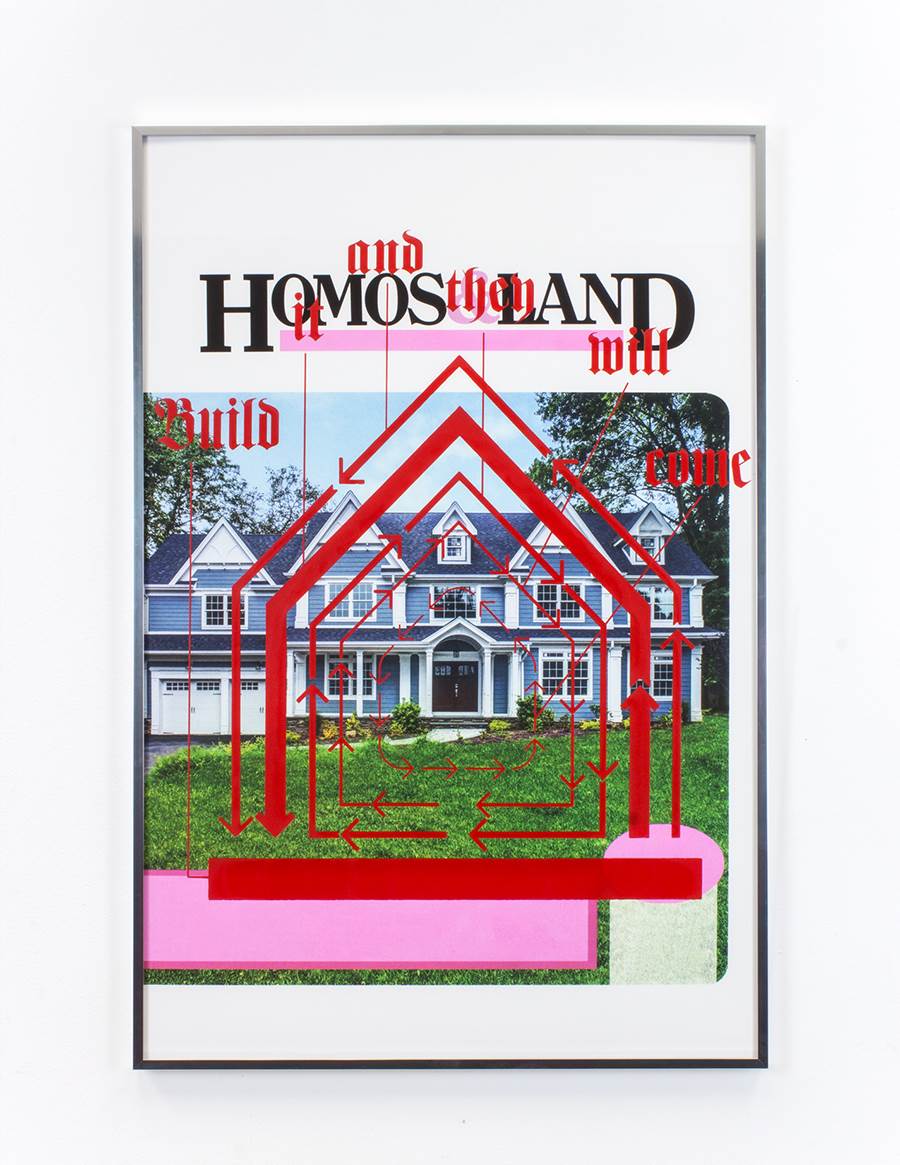

A.T. : In my work I have always critiqued that phrase. Home is such a sensitive subject for so many people, especially queer persons. Often we are left to build our own homes from various bits and pieces we can assemble, such as friends, and lovers. Real estate, be it for rent or to buy seems like the only thing which occupies the most space in our collective lives. It is so often that the topic of an apartment comes up in conversation, even currently. To me, rent is such an arbitrary system. What makes a one bedroom apartment more expensive than another? Is it built out of quality materials that will last under use? Does it include more amenities or is it nearer to them? Do you have control over the heating? Is it secure? These things seem to be fundamental to any rental or purchasable home but are often not factors for basic living conditions for the majority of populations. I would suggest that the exponential increase of rental costs globally is an affront to human rights. Our lives should not be tethered to exhaustive forms of labour just to be able to live in safe and secure housing. Rental increase immediately renders notions of difference mute. Cities have always been complex systems of diverse, divergent and complicated communities. These vibrant spaces are becoming more and more homogenous due to the overwhelming control of capital. Housing has become parallel with a bank account, as housing markets become a more viable place to let money grow under speculation. Most new buildings are left empty, yet housing access is becoming more and more limited and further and further out of reach. Quality housing is a human right, it should not be a factor of whether you work at an entry level position or are an educated professional, it should be accessible to all who need it. There have been many moments, and movements, which have introduced positive change to this narrative, I can only hope there is the necessary support for that change to continue.

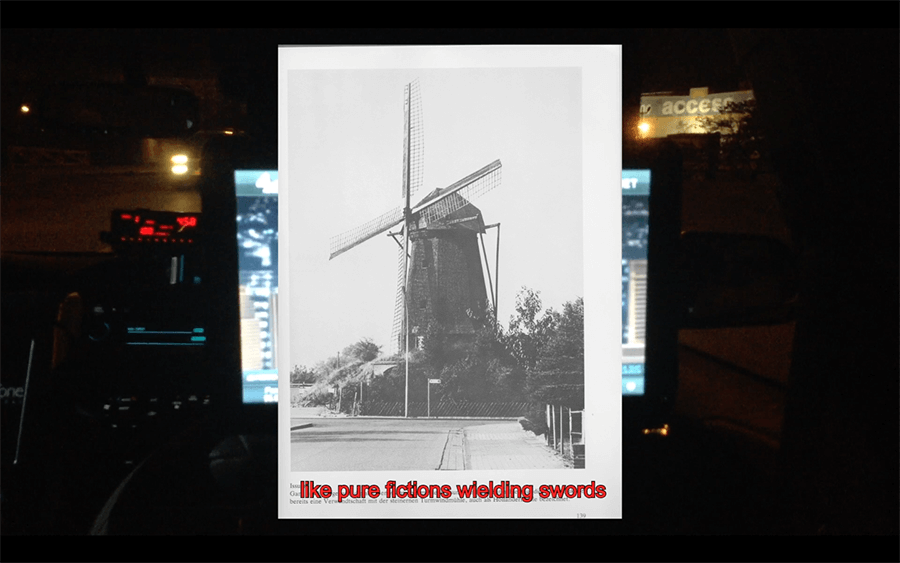

D.B. : Your questions raise some others, who decides the location of a residence or a shopping mall? Which practices of coexisting were displaced by that decision? What privileges and to whom does that newly built neighborhood grant? When we think of the city as a complex system as you suggest, how does your video work The Tilting at Windmills REDUX (2018) with its inspiring text, open up the conflicts of the system?

The Tilting at Windmills REDUX, 2018. 24’53” HD Video. Courtesy of the Artist

A.T. : That work really came out of residual energies that surrounded the 2016 US election. The poem was originally produced as part of a performance work of the same title at the Tate Liverpool in 2017. The later 2018 version was made as a way of archiving the language and visual archive that I had amassed in developing the original project. I wanted the poetry to exist differently as an archived version, rather than just as a recording of a performance. For me the performance was so much about the event, the relationships we developed as a cast of performers and the environment where it took place. I liked having that earlier version be ephemeral in some way, where the later video version was more an expression of the various source materials that I had originally worked with. As a poem, it was inspired by John Ashberry’s Finnish Rhapsody where the poet repeats the beginning part of each line by describing it differently in the second part of the line, however ultimately meaning the same thing. I wanted to take this further to a third variant, to produce a greater abstraction from the beginning. This was also intended to describe a loop: three points connect back to the first, creating a feedback loop. I wanted to express this process in writing and how it generates in echo chambers, mostly via social media. I was interested in how words can become reconfigured to sound different but ultimately mean the same thing. I utilized the image of a windmill as metaphor for this nefarious, self serving and antiquated presence. A subject which I imbued with the power and image of industry on a loop (because the mill stone rotates, etc). The title The Tilting at Windmills is taken from the phrase “to tilt at windmills” meaning to fight imaginary enemies. The phrase itself is derived from Cervantes’s Don Quixote where the protagonist attacks windmills thinking that they are mythic monsters to be slain. I wanted the windmill to occupy a similar space of the mythic and yet symbolize a language around authenticity which I feel is very problematic in North America and Europe. The symbol of a windmill is often applied to food packaging as evidence to its authentic, traditional style or nature. I think this kind of positioning and language becomes very problematic during times of heightened xenophobia in Europe and North America, where there are calls for a return to an idealized society where social, racial and sexual divisions were either established or cultivated. For me the windmills represented this very real, yet immaterial, monster which is generating a fear of change, a fear of resistance to the control, a fear of collectivity and a fear of difference be it racial, political, gender, sexuality, etc. The mill in this case can be a receptacle for any oppositional force looking to regain control over difference, change or equality. I wrote the poem with a specific intention to keep that definition open, but familiar.

D.B. : Architecture and language are the interconnected fragments, and sometimes the means of your work. How are they related to each other?

A.T. : I entered poetry through a material understanding derived from the study of sculpture. I was interested in placing objects, ideas, pieces and/or parts next to each other in a way that would articulate a language derived from their association. I approach poetry the same way—language as a material, either through the placement of words on a page or the placement of words in sequence. For me a poem is built, words are assembled, swapped, placed, carved. All of these terms I have just listed, either together or individually, describe a kind of construction. Once I began to think of poetry, and poetic writing, in this way it was natural for me to think about how architecture is assembled similarly. Both occupy a physical space that you can access superficially as an exterior (i.e. the surface), while offering the potential of interior access, though it's not a guarantee. There is an influential Audre Lorde quote where she states that “poetry is not a luxury, it is a visionary architecture.”[i] For me, this is a very powerful description of what poetry is and is not, it is not something that is frivolous, it is a formal structure to articulate the future—a kind of blueprint for world building. I think Lorde’s relationship to architecture here is that poetry has the ability to construct visions of change. Language is something very magical in that regard. I like to play with this in my work. Inversely I think there is an interesting relation also to how buildings describe a landscape for a particular public. You are either able to utilize these constructions or you are kept out in the rain. Each aspect of a building is scrutinized, like a poem, during its design to be the most potent form of its meaning, a statement to (and of) the world. I think that can be said not only about architecture as art but also buildings that seem generic, designed for cheapness and efficiency of construction, or seemingly undesigned at all (possibly by an algorithm). Each part is necessary for the overall function and appearance (be it rudimentary or opulent), its legibility, as a structure. I would say the same thing when describing a poem, each part is holding up the next, as well as the last, there is a structural matrix in which every part is necessary to keep the poem together. Again, I understand the nature of a building in the same fundamental terms.

D.B. : Such articulation of change, relying on the visions, performings of language, is inspirational. So, I am curious about the "poetic space of architecture" that you often identify your works within. Is that a queer envisage of yours? What do we need to understand about it?

A.T. : Similar to your previous question, buildings have a legibility. This is often explicit, such as its functionality, i.e. where the emergency exits are, but they are also very much monumental acts of individual expression. Buildings can be designed to impose an authority of power, empire, capital and permanence, or they can reflect prescribed ideals of living (among many other things). Lifestyle is a very Modernist reference, where spaces are constructed to dictate their intended purpose and use, which often fails due to the heterogeneous nature of society. Attempting to define a lifestyle that was designed in which all are to form to is apt to fail. We as individuals obviously operate and define our spaces differently as per our own needs, desires, identities and abilities (though I will say that design often does not reflect necessary requirements of accessibility). So all that being said, I read those architectural incentives, whether nefarious or utopic, as sites for poetic potential. I find inspiration in extrapolating language from built space, this language can be a result of acutal use or an aesthetic of implied use, it can also be how a building ages, evolves and erodes. How buildings are maintained also offer sites of poetic potential, the materials of care, the decisions one makes in how to patch a hole or move a window is similar to me as a gesture with a paint brush or a line in a poem. I am equally interested in what happens when built space is imbued with a kind of sexuality, an erotics, a queerness. This could be implemented in the design stage, but I am more interested in an approach to reading the building’s legibility. By queering the reading of a building, how might that change the understanding of its use? Is a rejection of a proposed use value a queer act? Can buildings be made in such terms and if so what then do they look like? What makes a building queer if all other buildings are not? These are the kind of questions that I continue to ask myself in my work. I hope those questions, rather than specific answers, are at the forefront of my art.

D.B. : Your works point out moral codes, decisions that make the space, and functionality are bounded. As any field in a world structured by social norms, architecture distributes the normative measures and discourse in return. Then, what could be the possibilities of queering the space?

A.T. : I think that, as product of this act, queer possibilities encompass space as metaphor for interiority and exteriority. Undermining the authority of normativity is essentially a queer act. Applying this to the power of buildings, or the dynamics of built space offers opportunities for iconoclasm, conceptually levelling the patriarchal methodologies which perform as established architecture or pending architectural development. I attempt to do this with language rather than so much as apply it to design strategies that are meant to re-interpret the formal layout of a building. In my work it's often this position of a single solitary subject made submissive by the monstrous. For me that interaction is inherently sexual, to be made submissive in the façade of power. Queering is the interaction, the exchange of body into space, of space as body, by reformulating that dynamic. In my work the image of architecture has always taken the place of the figure. So in that process there is an inherent queering of the subject because I utilize architectural references to articulate my emotional experiences as a queer, and gay, man. Rather than render the body, I wanted to utilize a form which has a kind of subjectivity and identity already integral to its representation, yet doesn’t visualize a specific erotics of a particular human form. There are already to many words used in construction vocabularies that are often used to describe an erotic body, I enjoy that play between definitions. I utilize these forms to consider the body as a building and the building of a body through processes of abstraction rendered by my poetic interpretation.

D.B. : Are there any efforts or works that you would like to mention in terms of design? Building not only gender-bending toilets corresponding to demand but challenging normative and customary values of architecture?

A.T. : I don’t really follow specific design studios or individual architects. I am interested in architectural theories and practices, but I am not looking at individual contemporary practices in particular, though I am not adverse to it. While I was doing my MFA at Rutgers University, I would often take the train down to Princeton’s School of Architecture for their exhibitions and corresponding lecture series. These exhibitions usually highlighted architectural practices that I think challenged normative modes, especially in the exhibition design itself. Which became, at times, more present than the actual work on display, which is a way of exhibition making that intrigued me. That all being said, the first exhibition I saw there was a very simple exhibition of Catherine Opie photographs. I remember something like four to six large format photographic prints in an already pretty small gallery. In the exhibition were a combination of two of her series Domestic and Houses and Landscapes.ii Domestic was a series she produced while embarking on a road trip around the US in the 90’s documenting queer domestic partnerships, along with another series Houses and Landscapes, produced around the same time, which documented upscale residential façades around Beverly Hills and Bel Air in California. As you can probably deduce, the exhibition really struck a chord with me and was very much in tune with my research interests as a graduate student. That conflation of these disparate societal documentations, the often DIY punk aesthetic of the queer domoestic scenes with these opulent, yet tragic, buildings of wealth didnt act as a longing for decadence, but described a form of wealth already present in the constellations of queer individuals (lovers, family, kin) as safe, secure and supportive.

D.B. : I imagine the accumulation of wealth over there! Such a genuine eye of Opie’s. Some of our previously displaced lives take place outside of the gentrified metropolises. The political quality of ones’ life that you mentioned (punk, artistic, gay…) and the survival practices (communal living, anti-consumerism, gift economy, etc.) identifying these lives are so often radicalized and excluded from residential neighborhoods, while even woods are becoming residential due to the commercialization of alternative living. Capitalism celebrates nature as wealth by remarketing the phantasm of the escape from the city. As a result, glamorous tiny houses of the bohemian rich and giant countryside constructions nearby the migratory, found, wild beings: queer. That conflation seems timeless.

A.T. : This is something really pertinent to my work moving forward. I’m so glad you articulated it as you did, this impossible escape from the kind of commodification you mention which seems so quintessentially post-capitalist. It's exactly that feedback loop, a kind of ouroboros—the snake who eats its own tail, that encourages the eligible disenfranchised (mostly the artist class, with the ability to move from one place to another) escape from the central urban space which has evolved to sanction a kind of displacement that enables being an artist not possible. There is then a move to more rural or suburban communities with the hope of having greater access to space, place and affordability. But that very act is equally a contributor to tactics of displacement, because it then others the local (even if the new additions to the community might be equally othered themselves). This becomes a narrative; taking over spaces deemed devalued to make them valuable, and is acted out, marketed and capitalized on. Phrases like “hidden gem” or “fixer upper” become equally applied and equally desirable. One might say a “steal of a deal,” but from who and at what cost? There are home reno shows which are specifically directed to this process. But also artists have always been the scapegoat for the socio-economic shifts in lower income, periphery neighbourhoods. Creatives move in, which generates a greater interest in the area, then it's only a matter of time before both the local community which initially resided there, and those who moved in looking for better access to sustainable living, are both pushed out for a kind of simulacra of the original culture which had previously been established there. Space becomes evacuated for the illusion of some intangible ideal. The whole process is this loop of self-consumption, there is something very mythological about how sinister that system often plays out.

Alex Turgeon. The Three R’s, 2018. Gif animation

Alex Turgeon, Homos & Land (Gentrify My Love), 2018. Screen print on digital print, 91.5 x 61 cm (Framed). Courtesy of the Artist.

D.B. : Built space and normative citizenship interpenetrate each other. Both complement the idea of persistency; rooting somewhere; a land, property, a relationship. Shall we talk about The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (2017), your work, a bluish interpretation of love and loss?

A.T. : As is with all of my work there are equal parts critical reflection and hopeless romanticism. As I was mentioning earlier, as in my poetry, there are varying levels of access to the content or root structure of my work. There is a convoluted network of associations, references and experiences. At times I would consider it as Janus-like, two faced in the sense that there is a tragi-comedy embedded in a project such as The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. That project was really a product of the architecture of the exhibition venue, Tunnel Tunnel, a former bus depot in the center of Lausanne in Switzerland. I was compelled by the very public nature of the space, one portion was almost completely walled in transparent glass, while the other was a retrofitted garage. I was very much interested in the inherent dichotomy between the private and the public aspects of both parts inherent in this exhibition venue. I wanted to make something which played with the level of access often provided to the street. With support from the gallery community we wrapped the glass façade in a reflective mirror foil, essentially reflecting the street back onto itself. As people would walk by on their daily commute or on their way home from the bar, they would see themselves in the glass in a much more pronounced way. Additionally I had letters cut out of the foil in forms of concrete poems which made the glass look as though it was broken, smashed through. The poems played with the multilingual nature of the location and were a play between French, German and English, often further playing with translation. Since the only parts of the windows which were transparent were the spaces where the text was removed, a curious passerby could peer through these small openings into the sealed-off interior. As a former bus depot, the ticket counter was still present in the space. I had made a looped video of roses being coloured blue, it was an intentionally violent act of blueing these roses because of the artificial nature of a blue rose. Which was another aspect of the romanticism I am speaking of since blue roses are a metaphor for unattainable love. These roses were dunked, painted, sprayed etc., and the video was broadcast 24/7 to the public on a small monitor behind the ticket counter, only accessible by peering through the holes in the window foil. Inside the former garage, I wanted to create a very intimate and romantic space. The visitor was greeted by a wreath made out of the blue roses from the video, a kind of funerary gesture attributed to the tomb. Once you turned the corner there was an entire wall of outdoor porch lights attached to the wall. These lights are often used in detached, single family dwellings, next to the front door or porch step. They often have a very generalized 19th century metalwork feel to them. While I was attending the last documenta, I was inspired by the brothels in Athens. They have a similar light fixture installed next to a very unassuming street entrance to the site of business. These lights are installed haphazardly, but indicate if the location of business is open or not. I was interested in turning a red light district into a blue one, and what kind of a mood or environment would generate out of there. From inverting the aesthetics of lust (red) to that of longing (blue) it shifts the very nature of this private a public space which the building itself is also performing. By bringing these outdoor lights inside, that dichotomy is further abstracted.

Alex Turgeon, Blue Light District, 2017. Exterior lamps, blue light bulbs, dimensions variable.

Installation view Tunnel Tunnel, Lausanne, 2017. Courtesy of the Artist.

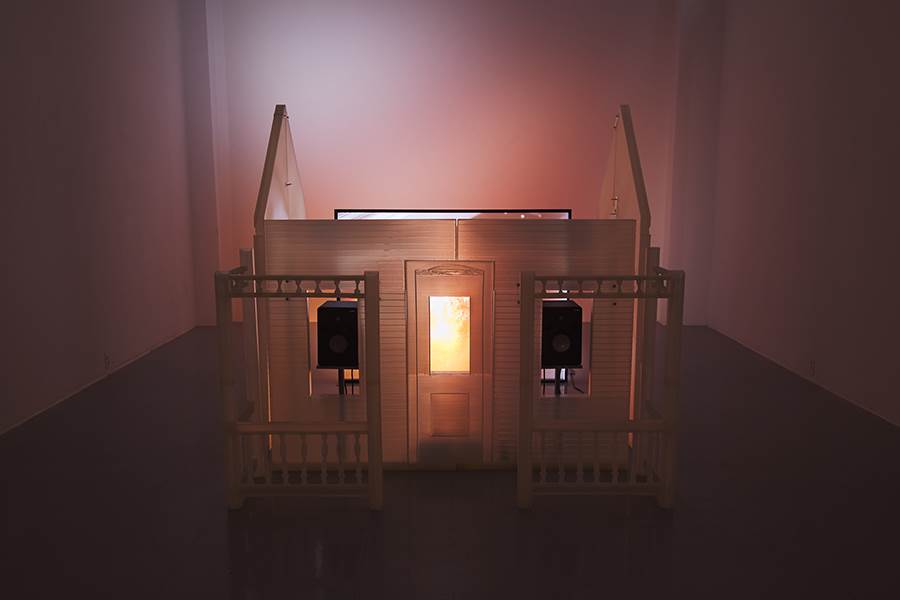

D.B. What your works also discuss is queer disidentification and politics of space. The Dreamlife of Vernacular Agents (Or My Life as a House); 2020, the sculptural video installation tackles sexual identity as if it is an architectural site. Can you tell me more about the site?

A.T. Firstly I will say that this work would have not been possible without the tremendous support of my dear friend Margaret Hewitt, who managed the 3D printing process of this work. As a result of that friendship, kinship even, this work was able to be realized, and for that I am eternally grateful. As a site, this structure has occupied my life in various ways, so much so that I had begun to see it as a metaphor for myself. It is essentially a playhouse made for children, which still exists today even though it is almost 100 years old. As an object it has been exchanged between people and has occupied different front lawns of various neighbouring homes. I used to play in it as a child, an act of formulating my affinity for domesticity often reserved for girls. Looking back it seemed to have been an integral aspect in the formation of my identity: as queer, as architectural representation, as image of something that it is not but still represents (it is neither a house nor a model, but both simultaneously). Its scale was formed to that of a child, but designed to evoke a real world homestead. There is something very compelling to me about that, and that it is a very accurate representation of a home not designed, or built, by an architect. So for me this site, and object, represented a kind of conflation of many things into one object. My intention with reproducing it through a 3D printing process was to pursue a process of translation. Decay became both evidenced in the representation, but also in various failures of the printing process. As a site which, as I mentioned previously, seemed to fundamentally from me as a person, I was interested in presenting this work as a kind of queer procreation in the form of architecture. The video which accompanies the sculpture, and forms the 4th wall of the structure, describes the erotic, bodily and visceral quality to the printing process, the machine becomes a kind of phallus which is extruding the translucent material that eventually constructs the image of a house as sculptural object. Surprisingly I opted to avoid including any poetry, but I think it is a very poetic interpretation of this (sur)real site.

The Dreamlife of Vernacular Agents (or My Life as a House), 2020. 3D printed PLA plastic, hardware and acrylic brackets, HD Video with rear projection: 15’36”, 211.5 x 183.5 x 166.5 cm.

Produced with generous support of Margaret Hewitt, Rutgers University, Autodesk Technology Center Boston and WOMP, Brooklyn. Photo: Jason Rusnock. Courtesy of the Artist.

D.B. Started working from home recently, people have experienced the exploitation of their labour as industries navigate the worldwide economic downturn. In countries where freelance work or working from home is rare, there are no regulations in terms of unpaid hours. Employers, on the other hand, assert that they have granted the risk-free option of working. Staying inside entails more domestic work and hosting employers and customers on the screen, at home all the time. It recalls quite an early portraiture of industrialization⎯working day and night, with no structural place for sleep, workers taking a nap on stalls, and above machines. When a house is still a house, but manifested by labour only, then how is its use-value assigned? And in your dealings, where would space head towards?

A.T. I really appreciate your framing of contemporary, pandemic, culture in terms of the industrial revolution. I would think that we are currently undergoing a post-industrial revolution, this is a conflation of both what you mentioned regarding the 24hr work cycle, where life and labour are so closely fused together and never ending, and the immaterial move towards labour. The establishment of the 40 hour work week was a 20th century invention, yet here we are rounding into the 21st and losing those labour rights before our very eyes (and screens). What is so apparent to me is this scapegoating tactic by corporations and employers that we collectively have to bend the rules due to the state of emergency the pandemic has provided. But I am left wondering when will that ever be remedied? Will things return to a kind of recognizable normalcy once the pandemic subsides? Industries have invested a considerable amount of time, money and energy in maintaining work processes during a pandemic, it would be equal if not more expensive to undo all of that newly established infrastructure. Why would a business require an office if everything can be done remotely? I am sure a it would offer a considerable amount of savings if providing a workspace was no longer the duty of an employer. I am left wondering about how this pandemic has, and will, fundamentally shifted the very nature of our society in a very permanent way.

D.B. I appreciate you sharing these activating aspects, as you do by claiming “decay is queer.” Built space and language, if both are the constructs, rooted and living, how might decay as a process come into play?

A.T. I define queer as both anti-normative but also as an inability to be, or exist in, normativity. I use the term normative as both associated with heteronormativity, but also how a system homogeneity can be applied to LGBTQIA+ communities. A rejection of normativity that I am articulating isn’t necessarily defined by extremes, though it certainly contains them, it is also an aversion to predetermined roles based on gender and sexuality. When I say “decay is queer” I think of upkeep, the maintenance of a particular aesthic, social position or class as a maintenance of normativity, which I would argue is in line with gentrification tactics—a process of forming complexity into simplicity. An inversion of that ideology seems naturally to extend to the idea of decay, overgrowth, erosion, because it makes complex the nature of an environment. There is something very normative to me about the necessity of maintaining a status quo, or the longevity of a thing, maybe like a building or a neighbourhood. I’m not sure, but to my logic decay offers a kind of romantic return to the beginning, a passive return to the origin of a site (when thinking about a building falling to pieces). That process feels oppositional to world building strategies where things are imposed, and meant to be there and be that way forever. I propose this declaration as a means of undermining late capitalist systems, which have evolved into forms of inclusion cloaked as tactics of normalization. Decay seems like a natural antithesis to that model.

D.B. Spanning various mediums; drawing, video, and installation, sometimes your final product is a poem or a piece of performance. I am thinking of your performance, which was held in the scope of your solo show Charon’s Obol (2016). With a microphone in mouth, you staged the space, installed with your works, while the audience watched from outside through the window of Center, Berlin. What does poetry do in the act of reading that refuses to generate meaning, words?

A.T. This is a very compelling question. Like an artwork, poetry has interpretive qualities that operate at varying levels of comprehension. There is often intent by the poet for words to form specific imagery, emotional fibres and sensory recollection (either all at once or in parts), but there are also the unique ways in which a reader projects their own experience, ideas, onto the words. I had the great fortune of teaching a class this past Fall at the art university near where I am living. Of course it was conducted remotely, but even so I think we were able to scratch at some of these ideas you mention. The course focused on poetry and its application in the arts through forms of social action, community and material. We experimented with poetic processes which are designed to do similar things, like at times refusing legibility, with writing. Specifically we used the “cut up” technique derived from William Burroughs and Brion Gysin. Students would take their stanzas that they had written and quite physically cut it up, authoring new abstract forms of their own language. This act further abstracts some of the, at times, more prose style writing the students would take on and breaks it further into pieces. This produced very poignant and beautiful abstractions which skittered the definition of legibility. That performance was about enacting a poetic constraint similar to that technique as performance. So the obstructing of the words I was speaking, by having the microphone in my mouth, was a constraint intended to render the text differently. I could have just been saying nonsense, but I was actually reading a poem about desire which is unobtainable, and so that rhythm, rhyme and pacing was very present in the reading. Emphasis was articulated by the level of force I inflicted through my voice so the result was a depiction of a struggle between communicating and failing to do so, and the frustration which arises from that internalized conflict.

Alex Turgeon. Performance documentation from the exhibition Charon’s Obol, Center, Berlin, 2016. Courtesy of the Artist.

D.B. Your research also involves the corporeality of poetry as computer code. Are there any affinities between queer thought and computer code, that comprehends, uses, and distributes language in its own way?

A.T. My relationship with computer coding is very introductory. This is not something that I am ashamed of in any way, it’s just that I am not a programmer. Due to that fact, my interest in incorporating digital aspects to my work is based on this rudimentary knowledge which produces a rudimentary aesthetic. I am quite compelled (and content) by digital aesthetics which are more foundational than cutting edge. I very much appreciate the skill and craftsmanship of complex and/or highly rendered digital imagery, but I feel an aversion to it in my own work. Perhaps my rejection of that aesthetic is similar to a rejectionist aesthetic/tactic, trying to go a different route, maybe even move backwards, against the grain. I used to co-run an independent e-publishing initiative called Version House some years ago. We played with this idea of distribution and the cumbersome nature of e-publishing in the mid twenty-teens. What really was compelling for us was that as a digital publication it is instantly and infinitely distributable. That was something we tried (my collaborator did all the programming) to architect for ourselves, rather than trying to format all of our content for mainstream platforms, we would develop our own web-based interfaces for accessing that content. Unfortunately I couldn’t afford to keep the site running after I dropped out of the project, so a lot of those projects are kind of lost in the ether of cyberspace.

D.B. I would like to recall Angela Davis' questioning of the sense of time which capitalism forces humans to think and produce withiniii. I believe there are people working against the capitalist understanding of time and space. Not happy about the things we created having been lost because of the financial impossibilities to continue covering the production cost of a project, but keep producing. You mentioned such ephemeral quality of a doing. I want to hear your thoughts about the act, the desire of creating something by knowing it will be lost. Staying inside, trying to survive financially, friends and colleagues connect, continue to produce works and artistic solutions of giving voice to the political and economical struggle everywhere. What do you think about the current state of art in general, and oursthe artist and art workers?

A.T. It is really a question about how art is consumed currently. Due to the acute remoteness of this moment, art is accessed almost solely by the image, the documentation of the work. It becomes a kind of currency. Documentation has evolved to really define the work of an artist, which I would believe is related to our ever increasing economy of images. Trading, sharing, promoting imagery which is representative of ourselves, and equally or our work, is very commonplace. But, yes exactly and to your point what about those things which evade this kind of economy? Must everything be boiled down to its exchange value? The narrowed distance between the artwork as it exists physically and how it exists as a representation is very pertinent to our current navigation of our prolonged stasis. I wonder if this is a true necessity, to have a physical record of a work? Does there need to be an immediate image of something once it is produced? Of course as artists we want to share our work with a public, but I wonder how that conflation between product and productivity shifts the nature of creativity? I think we as artists and creative persons make and be with art because that is what we do. It’s not something which can be removed and we function just as well, it’s part of our molecular make up. Art is an essential organ; it is always at work whether or not we are aware of it ourselves. Making art now, without a real sense of it being received by a public, is not necessarily an issue. The issue is making art in a vacuum, without the energies of our creative communities (and this too can apply to an online studio art education). There is something very necessary for the health of art, as well as the artist, to be part of something bigger than themselves. That doesn’t mean global domination, but that there is a community of exchange and support. Networks such as these are very much strained during this time while we are all looking for avenues of and for support, often finding ourselves floundering. I always think that the studio is at best a kind of birthplace, but for me the work is never completed until it exists out in the world. Before that moment the work is always in the process of being made. Once it leaves it becomes part of a world outside of itself, this is the moment which I think is really exciting, a moment I strive for. That energy is maybe loosely accessed through images, but for me it seems hollow. As an artist I make art because it is what I do and have done my whole life. I make art because I have a desire to interpret the world I perceive and respond to it through my person. I have work that I have destroyed because of moving or changing, but I would say that is all contained within the “ether” of my overall practice.

NOTES

[1] Quoted from Audre Lorde. The title of Lorde’s essay was first published in 1977 in Chrysalis: A Magazine of Female Culture. The opening prose of The Selected Works of Audre Lorde edited by Roxane Gay, W. W. Norton & Company; 1st edition (September 8, 2020), p.3

[2] Ibid. p. 3

[3] The installation shots and the information about the exhibition of the Catherine Opie’s series of photographs can be found in the link provided by the Princeton School of Architecture.

[4] “On Inequality” Angela Davis and Judith Butler in Conversation. “The panel took place at 2017 Oakland Book Festival, moderated by Ramona Naddaff, in Oakland City Hall's Council Chambers.”