“Can the contemporary suffering of individual bodies be viewed as an embodied collective reaction to life in late capitalism?”: Ania Nowak

14/04/2021

“Can the contemporary suffering of individual bodies be viewed as an embodied collective reaction to life in late capitalism?”: Ania Nowak

Gizem Aksu

Within permission of COVID-19 pandemic conditions, Berliner cold and personal psycho-somatic situation; we managed to meet face to face, heart to heart with Ania Nowak and pace together in Hasenheide Park. Steps melded into words, words melded into minutes, minutes poured into the trees with the joy of pacing together. As we sprinkled some thoughts and feelings on weird health, crip time, intimacy into hollows of trees; we have had a deep talk on choreographical approaches towards discursive power of word, text and silence; on nonnormative bodies and what life experiences and conditions of nonnormative bodies bring into the relation between art and activism; on how we can relate to the conditions which are nonobviously accumulated on our bodyminds by neoliberalism with(in) art.

Towards the end of our conversation; in order to get closer to her recent works, we played a performative game in which Ania drawed a card from the desk of questions. This card included questions quoted from the texts of her recent works and my recomposition of these questions into new and updated ones in the context of our interview. Some cards had some proposals for time or space to answer them.

She could not come to realize her site-specific artistic research in Ankara Queer Art Program because of the pandemic situation but I hope we will welcome Ania in Turkey soon. In addition to that it will be exciting to make artlovers meet with her unique artistic language and approach; I feel her presence would contribute into our endeavours with some choreographer friends in Turkey to open choreographic methodologies into the fields of visual art, text and video; to make them more accessible.

This Is an Exhibition and I'm an Exhibitionist, visuals by Pat Mic

Firstly, I want to ask how I shall mention you.

I usually say that I’m a choreographer, more recently that I’m an artist. I also sometimes say that I’m a performer, which would suggest that I can embody other artist’s ideas and desires. I actually preform in other people’s work much less than in my own. I invite people to perform with me, though. In the last 3 years, I started working a lot in the visual arts context. Since then, I realized that it might be easier to just refer to myself as an artist. But I went into art through dance, not through sculpture or video plus definitions can sometimes be quite limiting. They are also rather a requirement of the market than my own internal need. If I don’t call myself all these things, I can still do other things in the future, but language does this. It fossilizes you into a role.

Do you feel the invisibility of choreography when you just say I am an artist? In Turkey, choreography can be easily neglected or ignored. When you say you are an artist, people may not easily relate you to choreography.

Yes, absolutely. It is political to say that I’m a choreographer because in most places dance and somatic knowledge is still marginalised and at the bottom of art hierarchy when it comes to funding, for example. In Warsaw, where I worked a lot in recent years, there is a much smaller art and dance scene than in Berlin but they seem to be quite connected. On the other hand, contemporary dance and experimental choreography there are very dependent on theatre and its infrastructure. So whenever I am invited to a public discussion in Poland, especially in theatre context or in visual arts; I emphasize that I am a dancer even though at this point, I don’t have a typical dance practice based on a movement research in the studio. I definitely use many tools from dance, choreography and somatics in my text and overall performance work and I want to continue developing this kind of knowledge. I think it’s especially relevant in this moment we’re living now with the pandemic.

Are you an activist as well, or are you just using tools and engagements from activist histories in your work?

I am actually shy to speak about this because I feel there is a sacred and traditional image of an activist: it’s supposed to be this person who goes to the street and does action for social change.

I live quite comfortably in Berlin whereas in Poland basic women’s and LGBTQI rights are being taken away currently so there has been a lot of protesting since last summer, against complete abortion ban for example. I couldn’t be as active about it as my friends who actually live in Poland. Then, of course, there’s also the new problematic of protesting in the pandemic. Some countries, like Sweden, have recently made it illegal. It becomes very much about the risk one is willing or able to take to be out there. It means taking a risk when it comes to your physical and mental health while politicians are preparing shock doctrine in their cosy offices.

On the other hand, there is a very interesting text, Sick Woman Theory by Johanna Hedva, which speaks about those who are exempt from this traditional activism. Years ago, Hannah Arendt said that a political body is the one which is out there in public space, on the streets. We’re used to thinking that way about activism. Obviously this idea is rather reductive today. It makes you want to ask: but what about the disabled people, the sick, those with PTSD, those who are stuck at home? They cannot go to the streets because they do not have the mental or physical ability to do so. Especially as a queer person, POC or other minority, it means something else to present yourself in public space because you anyway carry minority stress symptoms in your mind and body and part of your experience is adjusting your public performance to avoid discomfort or danger.

I would say I have a lot of respect towards activist work. I also strongly believe, similar to Rebecca Solnit, that even though activism often doesn’t bring immediate results, it does accumulate its gains over time. It’s usually a slow process. I would say I use strategies from activism in my artistic practice to work with issues which are or need to be an object of activism today. Some of them are quite obvious, like all the issues that have to do with the rights of the LGBTQI and disabled communities, so against ableism and hate experienced by queers. I think I borrow strategies from activism also on a formal level, for example by working a lot with public speech format, like in my performance To the Aching Parts! (Manifesto), which deals with the delicate subject of difficult alliances within the queer community.

I practice the kind of soft activism that tries to invite and not to include. I still see activist and political potential in performance, ie. in performance’s ability to create space and give form to queer embodiment and experience, to propose ways of thinking and speaking beyond binaries. And on a practical, day to day level, I believe that next to acts of protest and civil disobedience, there is the whole and equally important work of care and support we do for our communities and ourselves. At the end of the day that too is a form of affirmative activism. Are you an activist?

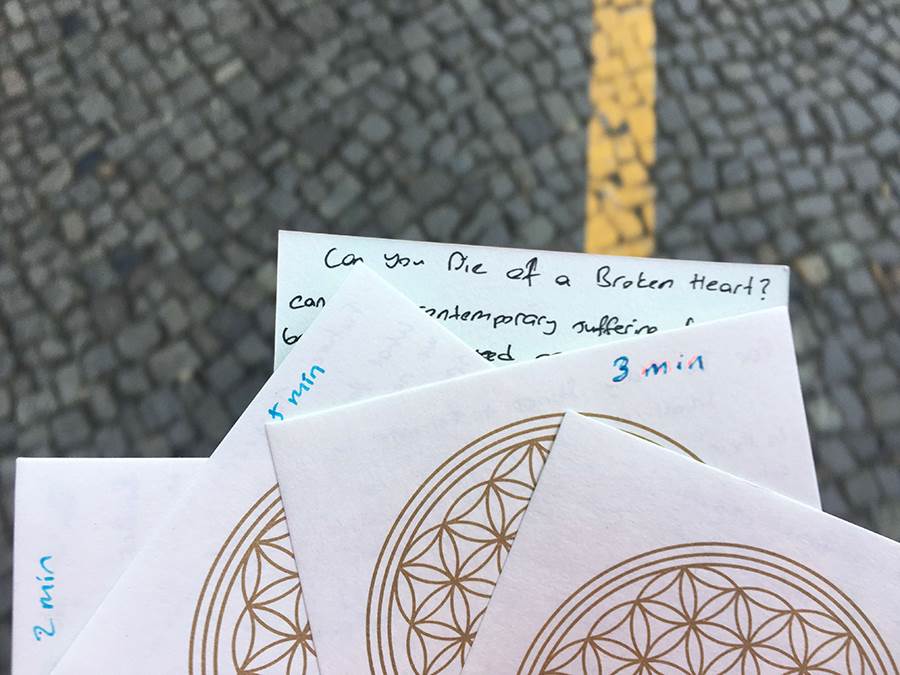

Can You Die of a Broken Heart?, visual by Bartosz Górka

Yes. In relation to previous question; the way that you are artistically working on pain, I had thought that you were also an activist. If this question sounds too personal, please adjust or we can skip it. You are frequently working on pain, fatigue. Does this engagement come from personal living experience?

In 2018, I started working with the subject of weird, erratic health, so focusing on health conditions that Western conventional medicine fails to cure or even treat. Auto-immune diseases, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome affect mostly women and are deeply systemic and psychosomatic. I got interested in them because of the autoimmune, auto-aggressive mechanisms of the body that harms itself in a way very difficult to pin down.

As with many other diseases classified in the last forty years, contemporary medicine is unable to explain their cause and likes to mention stress and trauma as triggering factors. When I got interested in them, I immediately started to come across people who experience them in their lives and realized that there’s discontinuity and weirdness in my own health too even though I usually take myself for granted as person with good health.

So two of my works, the exhibition and video Can You Die of a Broken Heart? and live performance Inflammations, deal with the personal and political dimensions of health. Two of the performers of Inflammations suffer from chronic conditions. One has multiple sclerosis (MS) and the other deals with debilitating gynaecological conditions that may cause chronic fatigue, loss of voice and other symptoms.

By the way, I really like Inflammations.

Thank you, it is one of the works I am most insecure about. Many people from the disabled community appreciated the work too. Because it is not didactic, among other reasons. It deals with poetics of illness, fatigue and their language but not in a victimist or heroic way. Even though there is more education about non normative health in our field, the approach is still incredibly ableist and so it focuses on inclusion rather than on exchange and invitation. Audiences still have very particular expectations both when seeing healthy and sick bodies on stage.

Inflammations, visual by Dorothea Tuch

I agree with that.

Sickness or weird health can become your identity, also as a strategy of harnessing your incoherent bodily experiences in the long run. How to make sense of something that your doctor tells you is chronic? With those two works and through the exchange with my performers-collaborators Angela Alves and Laura Lulika, sickness became a lens through which to perceive and do things in another way, rather than a curse or a taboo. Those processes made me more aware of my own physicality and the degree to which I’m used to accepting pain in my life on regular bases —for example the physical and emotional pain caused by PMS, period and maybe endometriosis— as a natural thing that cannot be helped. Then Coronavirus came and made many people shift their understanding of where sickness begins and ends and what solidarity is. When I think of the dance field, you are required to be on top form and healthy all the time. You are expected to mask illness. If you are fat, it is not okay, because you don’t look a certain way. If you are disabled, it is not okay because you might be slower or need care. I started thinking how this excludes other ways of being in your body.

When I tried to tour Inflammations to different places, I learned what the situation of a working disabled artist can really feel like. Venues don’t want to pay for a carer to accompany a disabled performer because it is an additional cost, even though care work is paid less than the light designer’s and equally important. When working on and rehearsing Infllammations, it was important for me to respond to the needs and boundaries of my collaborators but also to set my own limits. So we did shorter working days (as opposed to the usual 8- or more-hour-long days) and really tried to embrace crip time. Often when you initiate and mother a project you end up self-exploiting anyway, that’s a bit the assumed dynamic of artistic production. I struggle with that too, I must admit.

For me, it was so obvious the piece was proposing an experience of crip time to audience and I really enjoyed this proposition.

You know sometimes, it is really not easy for me to talk about these things because on the one hand, I don’t want to speak for the disabled community which is, in any case, not homogenous but on the other, health is such an unstable and incoherent space and a part of literally everybody’s lives. Angela once told me: ''Sometimes I suffer because I have MS; other times it’s because I have PMS. You say a lot that you have very bad PMS. It’s the same shit.'' I loved that.

Super. You know sometimes there are things that can not learned through dictionaries; only learned through experience and by living together. This kind of learning-together-process is so valuable. These processes can open research and resources that you can think on the definitions that you gave even for yourself.

What struck me when I started working with Angela and Laura for Inflammations is how political they are about their disability or sickness. The process of learning from the disabled community has been crucial in my personal and artistic life. It’s hard and pessimistic to realize that the whole system and environment we live in and that we constantly reproduce under capitalist patriarchy is actually making us sick.

The possibility of crip time is not something concerning only disabled people. I believe it is actually a proposal for this life in late capitalism.

I believe discussions on crip time will come more often in coming years. I am observing that it has been started to be discussed in different circles.

Coming question is about the usage of text in your works and discursive power of language, words and silences. In your work, I really appreciate how you are using repetitions, linguistical reverberations of a word into another and transformations among words in which I would say this becomes a signature for you in last 3 years especially. In each pieces, it was there in a slightly shifted way. How did you start to use this rhythmical and repetitive approach to text?

I think language is fascinating when you start to work it choreographically, a bit like it’s dance, for example by applying simple tools from dance composition to it, such as repetition, reverberation, slowing down or speeding up. One day in the studio while working on a new piece in which I knew I wanted to fiddle around with drag and language, I just started playing around with groups of words, making lists of four words that were associations on a given subject. It was quite fast paced and restricted. I would mostly use nouns, names and numbers. I ended up making improvised, very ephemeral and weird verbal images that related to Polish and European history, politics, sexuality, etc. I realized I could either keep making up this text material like a dance improvisation or write it down. I slowed down, wrote it down and it became Untitled, a work I made in 2017.

.png)

To the Aching Parts! (Manifesto), visual by AnuCzerwiński

In a more recent one, To the Aching Parts! (Manifesto), I focused on sets of three words to try and escape the binary and always use a third element to destabilise the other two. I also worked with verbs and actions more than nouns. But still I barely used sentences, prepositions or conjunctions. They were all lists of single words where the meaning or the expectation of what something might mean shifts all the time. I also worked with acronyms in that one, also in Inflammations, precisely on deciphering some acronyms we know, like LGB, FtM, DIY, PMS, in a new way.

Because the words are made into lists and they don’t form sentences, this kind of text is actually really hard to memorise. So when I perform it, I usually have it written on paper, which really becomes a prop in those performances. They are staged like a public speech. I am interested in what the word triggers on the level of meaning and how it can alter its form when we refer to ‘truth’ or truths. It is a good moment you are asking me this question because later this year, I will make a new piece and I want to take the language practice a bit further or somewhere else. Don’t you think language is actually much like movement?

My relationship to language is a bit conflictual. When I was studying political science I realized how much cost the language has brought in political fights. Therefore, I started to move actually.

Concerning language, I realize it’s really a solo practice for me, even though in some works I wrote text for the performers and enjoyed performing it with them a lot. In Future Tongues for example, I worked with gesture, touch and intimacy which evolved into speech towards the end of the piece. When I’m busy with the public speech format, I’m also very specific about the gesture to accompany language. I guess then it becomes about a strange kind of intimacy which is not about possible proximity, affinity or tenderness (not that intimacy is always only about that) but rather about me trying to touch people with my idiosyncratic language made of word associations. So with a language that is not necessarily a common construct understood by all. This complicates intimacy. I put myself out there to charm or trick people into believing what I believe, even if these beliefs might not be popular, and I know that I will partly fail at dragging them to my side. The seduction implied in a performance situation can only get me that far. Words mean more directly than movement sometimes. Language performance in the visual arts context is also a way of escaping the objectifying role I’m put in as performer-art work in the white cube. I think I can problematise this unequal relationship between the spectator who gazes and the performer who is seen by using language and gesture in a very specific way which has the capacity to turn the spectator’s attention onto themselves and the object-art works in space.

Would you like to share your recent interests, including your participation to the residency of Ankara Queer Art Program?

For Ankara Queer Art Program, I was going to do a site-specific research into queer culture and its clubbing aspects in relation to the aesthetic and affective tropes of Baroque style present in Turkish architecture. Unfortunately, it hasn’t been possible so far, because the pandemic made it impossible to travel to Turkey.

Currently, I am busy looking into queer grief and its rituals since the AIDS crisis of the 1980s until today, till this moment of COVID 19 pandemic. I am going to make a new piece about it at the end of this year. I am also wondering about the relationships between strong language and weak bodies and about practices and images of endurance, stamina and even heroism that minorities engage with today and if so, what is this heroism about?

I feel that this year, even more than before, I focus a lot on durational, invisible processes linked to sickness, ageing and living in late capitalism. I’m interested in micro transformations within longer processes, be it the process of grief, a pandemic or emancipatory social changes that minorities participate in.

Play Part

From the Text of Can You Die of a Broken Heart?

Can the contemporary suffering of individual bodies be viewed as an embodied collective reaction to life in late capitalism?

My Question: Can you please open how suffering can be transformed to actional/reactional subjectivities? Can you name some collectives/circles/environments/organizations which inspire or empower you by doing this, if any comes to your mind?

Speaking out about an actual need for change when it comes to subjects like disability, health, care and non normative bodies is a relatively new practice in my field and circles. Being more open about mental health issues in the dance and art field is also a change prompted by the pandemic. There are more and more voices in the disabled and queer community in Berlin that are trying to stress the necessity for structural change in how we work and operate to make the field more accessible to other people than white, able bodied, middle class Europeans and Northern Americans. It’s a complex discussion, though. When it comes to performing arts institutions in Berlin, Sophiensaele seems to be the one most determined to introduce accessibility strategies for audiences with different kinds of disability. By this I mean everything from audio descriptions of performances to German or English sign language interpretation or the relaxed performance format. In a relaxed performance spectators can come in and out of the space as the show is running, if they need a break, for example. It’s an attempt at making the performance situation more comfortable and hence accessible.

I’m not linked to any specific organization or collective at the moment. I do learn a lot from people I collaborate with, though, like the whole team of Inflammations, as well as from artists and activists I cross paths with in different contexts. I think that this kind of open communication about lived experiences and needs is crucial for me to become more aware and to be available to different kinds of people and situations. Empathy is a word used a lot nowadays. And empathy is labor, it’s actually exhausting. A lot of emotional energy goes into it, especially in our queer communities where there’s a lot of talk about trauma and it’s easy to spiral down if you don’t feel held by others sometimes. The more I think about what a better life could be like, the more I realise that one of the preconditions for an embodied change is to do away with self-care, as we understand it in the West, and develop actual unconditional self-love. The kind of self-love that adrienne maree brown writes about in Pleasure Activism. To stop apologising for our bodies, our desires and our rights, for not willing to over work and be exploited. This radical self-love —my goodness, it sounds so hippie!— is so hard because we are conditioned to believe that attention, acceptance and affection is something that needs to be deserved and that we only deserve it by obeying the rules of capitalist patriarchy. This system dictates who is actually worthy of love and empathy but also who gets to be left out of dominant stories of love, empathy and grief.

Future Tongues, visual by MaurycyStankiewicz

From the Text of Future Tongues

Please answer for 5 mins and under the oldest tree around.

What forms of embodied communication do we need today? Who has the right to speak their own language? Can we trust our collective intuition before we obey the authority of knowledge and power?

My Question: Do you have any daily rituals for feeding your intuitional power? As an artist working on intimacy and intuition; what do you think on how they are related to each other? How do you approach this relation in your works?

Rituals and routines are not so easy for me because of my tendency to self-sabotage. It’s as if I couldn’t commit to anything that would actually make everything better. With the help of dance, somatic techniques and friendship structures I have become, I am becoming, better at it, though.

On a psychological level, I’m currently working on harnessing my internal chatter, so the multiple dialogues or monologues that go on in our heads. I feel like I need to become more aware and in charge of my mental chatter especially in these pandemic times when being just with yourself and the social media is something you don’t always choose. I think part of it is because I want to focus on the kind of communication with others and myself that is not detrimental to my mental health. I’m not good at letting go. That’s why I started dancing when I was much younger and it’s something that stayed with me as a strategy of distancing myself from overthinking, for example through club dancing, until the pandemic started.

Currently, I try to stick to Feldenkrais Method, so to a somatic technique. I chose this one because it doesn’t tell you what the movement should look like. Rather it invites you to experience the sensations it brings and to develop your self awareness in the process. You do this through instructions you hear and you interpret them through movement. In a way this is how intuition works, isn’t it? It’s based on past experiences. It doesn’t give you clear answers, but it offers you hints.

The relationship between intuition and intimacy is an interesting theme for me at the moment because in recent months I have accepted that I am good in my life when I trust my intuition as opposed to when I question it. If you belong to a minority, it is political to be direct about what feels good to you and what doesn’t. And then, just because something feels good to everyone else, it does not mean it needs to feel good to you too. When I initiate processes with other makers and performers we often work with soft hierarchies. We get to learn about our personal boundaries and vulnerabilities as we go. It can get hard sometimes. In any case, it’s crucial for me to approach performers in a way that is free from the psychological violence so often practiced in the theatre. That’s why I constantly check in with myself and follow my intuition to be able to check in with others better.