"Act like the ocean floor": Interview with Erin Johnson

10/06/2021

"Act like the ocean floor": Interview with Erin Johnson

Kevser Güler

The lines below are extracts from written and online conversations that took place between Erin Johnson and Kevser Güler between February and May 2021. The pandemic triggered shifts in temporality and their conversations were interrupted, returned to days later, impacted by a sense of instability and discontinuity, and shaped by digital media contingencies. While taking into account the unevenness between the situation in New York and the situation in Istanbul, and in the individual lives of both participants, the conversations unfolded through a shared curiosity in modes of surviving together, and sustaining artistic production and the everyday life of artists and communities of art.

Erin Johnson, Lake (2020)

KG: Your proposal for Ankara Queer Art Program Artists Residency was based on developing a screenplay about three young, queer women artists as they navigate relationships with collaborators and partners living across the globe during the coronavirus pandemic. Since you made the application during the very first weeks of the pandemic, how has this project changed?

EJ: Because of the difficulty of filming with others, I pivoted to filming myself over a three-week stay in a modernist house in Maine.

Renowned science writer Rachel Carson described the ocean as a space with “no finality, no ultimate and fixed reality,” connecting distant shorelines with its “unifying touch.” Like Carson’s account of the sea, I’m working on a new video installation that will bring together two disparate subjects that abound with uncertainty: a modernist house designed and built by two women and the current attempt to map the entire seafloor by 2030. By investigating gaps in archives and scientific research, the video will address questions regarding indefinability, erasure, and queer resilience.

Built abutting what is now the Rachel Carson Preserve, the house was designed in the late 1960s by what I speculate was a lesbian couple - painter Beverly Hallam and art collector Mary Leigh-Smart - who potentially wanted to appear as though they lived separately. They made two apartments connected by twisting and shadowy corridors and I shot footage of myself moving through, and tending to, the house.

In 2021, we know more about the topography of several planets than we do about the surface of the earth beneath its waters. Due to the limitations in sonar, laser, and sensor imaging tools, more than eighty percent of the World Ocean floor remains unmapped. Right now, there is a global effort to map the seafloor by 2030 to better understand how the ocean affects life on land (particularly its role in climate change), and what is happening in the depths. I’m particularly interested in seafloor spreading, the process by which the ocean’s floor is constantly creating and destroying itself.

The cyclical nature of this process of making a whole out of parts, and back again, becomes a lens through which the video explores the act of finding ourselves in the fragments left behind by others. As the voiceover weaves together things about the house and the seafloor, it will explore queer accounts of ocean ecology and the work of making visible the invisible.

This new work - which has been shot and in post-production - builds upon my recent research and projects. For example, the video I might not be here when you come takes as its starting point Solanum plastisexum - an Australian bush tomato whose sexual expression appears to be unpredictable and unstable, challenging even the fluid norms of the plant kingdom. Footage of the Solanum team of botanists as they sing lines from their research is combined with shots of Australian plants cultivated in the United States. In Salidas y Entradas Exits and Entrances, elders use public senior centers in El Paso, Texas as a stage to perform dynamics of the militarized U.S.- Mexico border, the desire to be seen, and gender as performance. Heavy Water follows a Department of Energy biologist studying the effects of radioactive waste on animals living in a nuclear weapons complex, bringing together the precarious future of nuclear weapons and the uncertain past of a wild breed of dogs living on the site. In the multi-channel videos Lake and Tomatoes, a group of friends, peers, and lovers engage in collective queer and desirous exchanges, such as eating tomatoes in a field and floating in a lake.

.jpg)

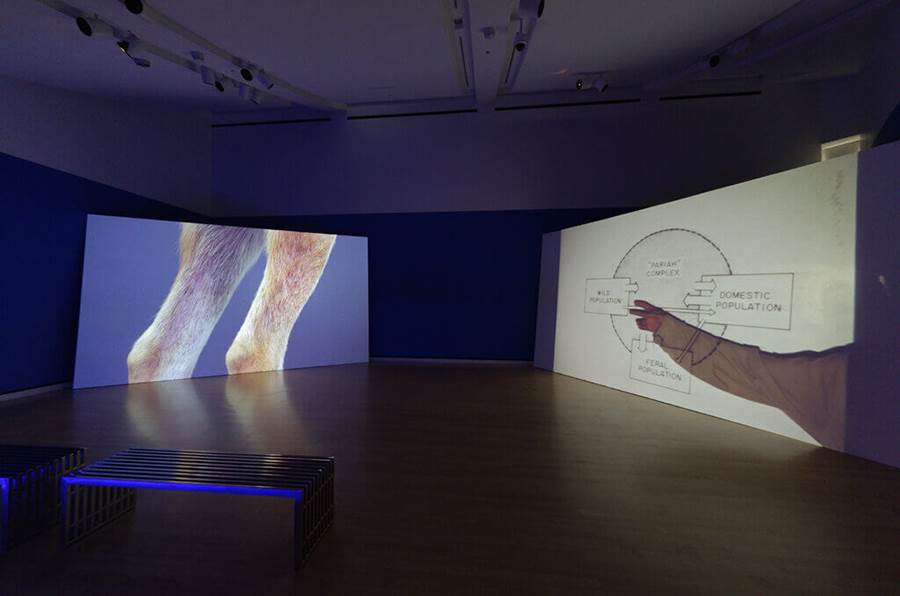

Erin Johnson, Exists and Entrances (2018), Installation views from Both Players Move, SPACE Gallery, Portland, ME, 2020, 25:57 multi-channel video

KG: It was a joy for me to discover your site-specific works. How do you think the contemporary conditions of the pandemic will impact your way of conceiving a video?

EJ: During the pandemic, I opened a piece at Midnight Moment in Times Square. Lake gazes down at a still body of water from a birds-eye view while a group of artists peacefully float in and out of the frame or work to stay at the surface. As the swimmers glide farther away and draw closer together, they reach out in what the artist describes as “collective queer and desirous exchanges” — holding hands, drifting over and under their neighbors, making space, taking care of each other with a casual, gentle intimacy while they come together as individual parts of a whole. The video reflects on notions of togetherness and feminist theorist Silvia Federici’s call to “reconnect what capitalism has divided: our relation with nature, with others, and our bodies.” I became interested in how groups of people, in this case artists, live in relation to — and support — each other. The gestures and movements in the video reflect the interpersonal and group dynamics present in this kind of collectivity: each person’s movements impact the others as they try to remain close while giving each other space, attempt to stay in the frame, and hold each other up when sinking. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, however, this video has taken on new, additional meanings: the suspension of time, the feeling of being adrift in space, and the importance of intimacy and proximity.

Erin Johnson, Heavy Water (2018), Installation view of Heavy Water, Telfair Museums, Savannah, GA, 2018, 15:36, multi-channel video

KG: For your videos, you employ documentary, experimental, and narrative filmmaking devices, and look at the ways people gather, stay together and engage in doing things all at once, collectively. It’s a kind of a thread that may be traced through your practice. In your video installations, via the tiny details of the encounters among the people, the space they inhabit and non-human animals, plants and materials accompanying each other, the questions about the ethics and politics of interactions unfold. And one of your recent projects that you’ve mentioned, Lake, is quite layered in those terms - people trying to stay still in a lake, in suspension, close to each other, caring about their bodies proximity with the person closest to them....would you tell more about the project? How it all started? I believe in the days of global pandemic, this video has extended its reach...

EJ: I made the work while in-residence at Skowhegan School of Sculpture and Painting, where I spent nine weeks with an incredible group of artists. By the end of our time together, I wanted to film the group engaging in something that thought about precarity and support. Graciously, many friends and colleagues agreed to join me in the lake where we tried floating together.

The piece was recently exhibited at Midnight Moment in TimesSquare, the world’s largest, longest-running digital art exhibition, synchronized on electronic billboards throughout Times Square nightly from 11:57pm to midnight. We decided that March would be a nice time because of the Spring Equinox, the promise of warmth and, hopefully soon, more chances to gather together safely.

Erin Johnson, Exists and Entrances (2018), Installation views from Both Players Move, SPACE Gallery, Portland, ME, 2020, 25:57, multi-channel video

KG: One of your first videos The way things can happen already introduces your precise forms and approaches of producing and engaging with a collective experience. Presenting people providing alternative, subjective, sometimes slightly contradictory versions of the same experience of the shooting of the 1983 film The Day After. The way things can happen complicates the representation of a city through its inhabitants’ narrations of this event which took place 34 years ago, and untangles the fluidity and temporality of images in a way. What brought you to the project? And what were your aspirations before you had actual shots?

EJ: I went to Kansas initially to look at the LGBTQ archives at University of Kansas. There was a large anti-nuclear movement in the area and many of the organizers were also doing queer rights work. I was excited about the overlap but not sure where I wanted to go with a project. I went to meet with the director of Lawrence’s historical society and saw images of town turned into a movie set and started thinking about how these images of this fictional thing was made real and had entered into the archives. The director introduced me to a group of people who had been in the film as extras and we started talking about film as a way to try things out, to encourage different outcomes for the future.

Erin Johnson, Tomatoes (2020), Installation view from Unnamed for Decades, Center for Maine Contemporary Art, 2020, 4:26, multi-channel video

KG: And your video Tomatoes - it also so subtly and almost meditatively gets one watching, imagining queer strategies for surviving together, with all its joys and empowering fragile support structures let’s say.. eating, touching, exploring, collaborating, kissing, organizing, playing, loving.. Collectively. In collaboration, in friendships, in love.. what has been the story behind this piece of yours?

Similarly, I made this piece at Skowhegan, along with the project’s creative director, painter María Fragoso. That summer, I spent more time looking at paintings than ever before and started to print out images of feasts, of bodies sharing in abundance. María started pulling together a series of historic paintings too and we used them as references for the artists who participated in the video to spark their performative gestures.

KG: I think the monochrome elements of your video installations suggest a subtle extension of the video into the space. This seems like a painterly gesture which I have been attracted to from the first moment I recognised it. Would you like to comment on this? This way of suggesting almost a geometrical abstraction driving from the video, from your look?

EJ: I think that my projects really are experienced best in installation form. I generally work in multi-channel, a form that doesn’t work as easily online. I think about multi-channel as a formal way to acknowledge the contradictory nature of all the things I’m interested in – or at least the different ways that one can approach them even if they’re not contradictory.

KG: Throughout your practice it is common to encounter works tackling the queerness of nature. How do you think the pandemic informs your practice in terms of the idea of the nature that resists the binariaries?

EJ: This past summer, I wrote the following in an essay for a friend’s show catalog and I’m thinking about it in relation to this new video I’m working on:

Yesterday, I spoke with an oceanographer who told me that less than eighty-percent of the seafloor has been mapped. In addition to being unknown to humans, the seafloor is in a constant process of creating and destroying itself. Tectonic plates split at their boundaries and slowly move away from each other. Hot magma bubbles up and glides into the fractures and is cooled by seawater, becoming rock. The rock becomes a new part of the Earth’s crust. And then this process, called seafloor spreading, begins once more.

As he explained this to me, I thought about Maria Tinaut and the archipelago of scattered broken tiles she found in the field behind her house, their blue flowers, once whole, now a sprawl of broken petals. She brought them to her studio and looked for where the winding, faint lines had originally joined, and tried to bring the disparate parts back together. “To be a good human being,” philosopher Martha Nussbaum said, “is to have a kind of openness to the world, the ability to trust uncertain things beyond your own control that can lead you to be shattered.”[1] But what happens in the wake of the kind of breaking that Nussbaum describes? Tinaut’s piece Blue 1 - a few dozen pieces of almost-but-not-quite matching bits of tile closely embedded in gray joint compound - offers one answer: act like the ocean floor.

Erin Johnson, Heavy Water (2018), Installation view of Heavy Water, Telfair Museums, Savannah, GA, 2018, 15:36, multi-channel video

KG: I feels like your practice tackles the structures of knowledge and the ways they could be altered in a realm emerging between individual lives and sociopolitical conditions. Knowledge is not without problems, especially these days in knowledge capitalism. What I found so powerful in your practice is your ways of creating entanglements through various types of knowledge building - letters, stories, dialogues, memories, schemes, archives, and fictional narratives coming together, suggesting an invitation to contemplate and experience the place and the time when different forms of knowing appear and disappear, knowledge making itself graspable or just fading in relation to power and communities. And I guess this works like a critical method for queering the ways in which knowledge is produced today. Would you agree with what I have felt?

EJ: Absolutely - I would love to talk through this one more with you through the next conversation of ours!

KG: To elaborate on the reason which brought us together, how have you decided to apply to Ankara Queer Art Program residency? Have you ever been in Turkey or are you familiar with the queer art practices in Ankara, or Turkey at large? What have been your anticipations regarding the application? And how do you feel about the necessarily adopted format of the online residency now.

EJ: I’ve never been to Turkey but hope to visit soon. I’ll be at the Jan van Eyck Academie starting in June 2021 and it would be incredible to come stay in Turkey during my time in the Netherlands. I’m sad that the residency wasn’t able to be in-person yet, but I still hope to come!

[1] https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/07/25/martha-nussbaums-moral-philosophies